Energy: Can Nepal reliably reduce fuel imports?

Nepal urgently needs to cut down on the import of fossil fuels from India to check the rapid depletion of its foreign currency reserves and thereby forestall an economic crisis. Fuel accounts for 14.1 percent of Nepal’s imports, and reducing its import will help the country save its foreign currencies and to minimize the trade imbalance with India.

Replacing the traditional sources of energy with cleaner ones is also an imperative in order to curb the worsening air pollution and combat climate change.

On paper, import reduction is a major government priority but in practice, it is just the opposite. Our import continues to balloon by the day due to poor implementation of policies.

Nepal’s import-reliant economy is unsustainable, particularly when oil prices are skyrocketing and global supply chains have been disrupted by the Russia-Ukraine war.

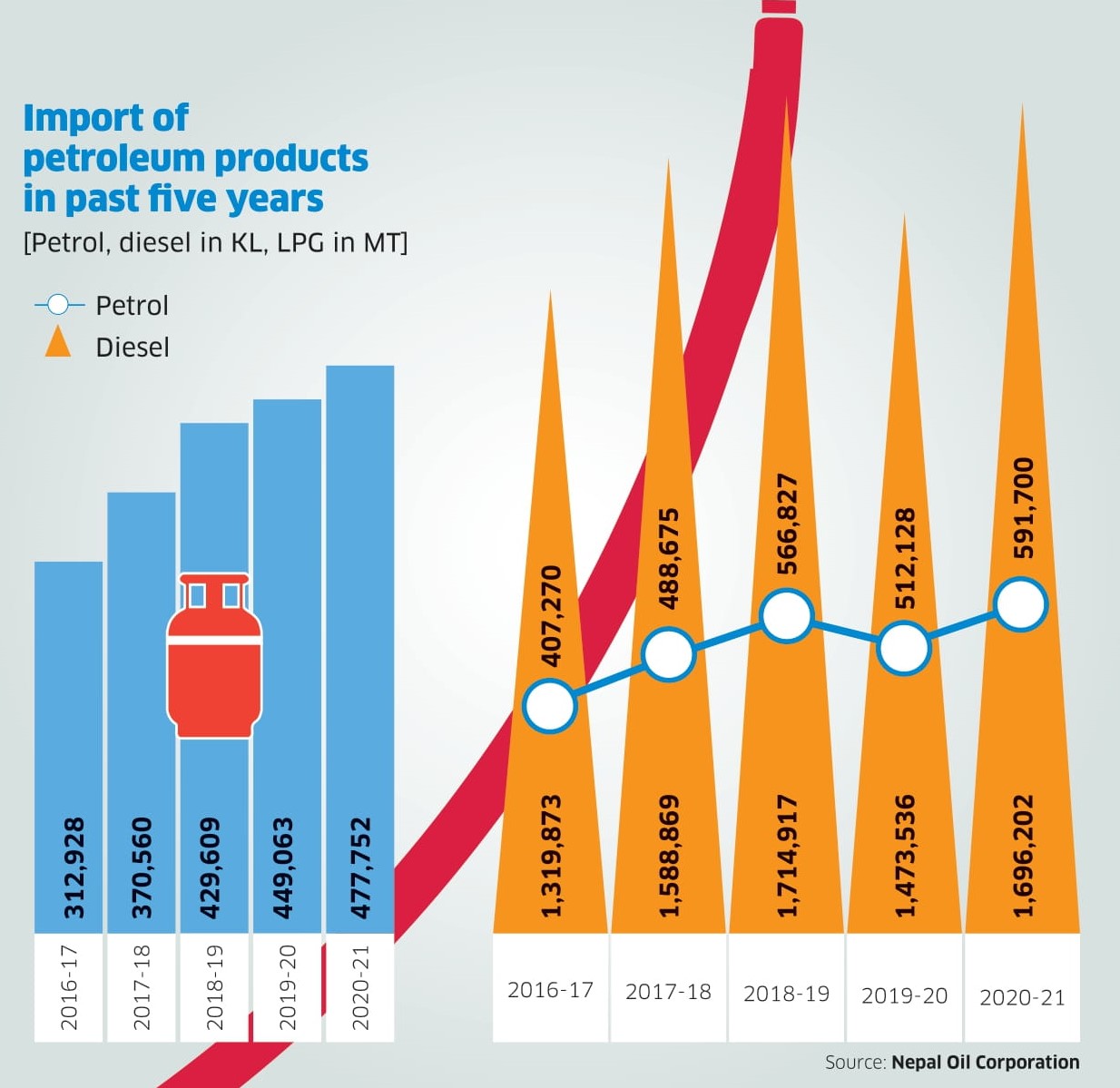

Government figures suggest significant import reduction is unlikely in the near future. According to the Economic Survey published by the Ministry of Finance (2020-2021), among the petroleum products, diesel is our chief import. In the fiscal year 2019/20, diesel made for 57 percent of the import-volume followed by petrol at 20 percent, and LPG at 17 percent. Likewise, aviation fuel made for five percent of the mix while kerosene made for a percent.

Meanwhile, the import of LPG is also increasing as gas stoves rapidly displace biomass and other traditional sources in rural kitchens. According to Nepal Oil Corporation, in the past two decades, LPG imports have jumped by 2,466 percent.

It is not just fossil fuels Nepal imports from India but also half of the total electricity it consumes during the dry season (the country also exports its surplus energy to India during summer).

Nepal currently produces 2,200MW of hydro-electricity, and plans on ramping up production to 10,000MW over the next decade. But during the dry season, our hydropower stations generate only a third of the 2,200 MW while the peak demand is around 1,700 MW. Nepal then has to import around 800 MW from India.

“With some hydropower projects close to competition, there is a hope that Nepal can stop importing electricity even in the dry season. But this could take three to four years,” says Sushil Pokhrel, a hydropower expert and the managing director of Hydro Village Pvt Ltd, a consulting company.

According to Energy Minister Pampha Bhusal, 94 percent of Nepali people have access to electricity but our per capita electricity consumption is just around 300 units a year, which is the lowest in South Asia.

Bhushal is hopeful that Nepal can produce an additional 1,000 MW of electricity within the next couple of years.

Producing more electricity is one thing. But will the produced power be optimally used? And can it replace fossil fuels, so that we can reduce our import of petroleum products?

Energy experts say extreme situations demand extreme measures.

First, they say, the government should promote the use of electric vehicles (EVs) to use up all the surplus hydroelectricity. They advise all local governments to take such measures.

The number of private electric cars is increasing, which is a good start. Greater use of EVs in public offices would be a good second step.

In its policy document, the Energy Ministry says 25 percent of all private passenger vehicle sales, including two-wheelers, will be electric by 2025. It also aims to push the number of four-wheel public vehicles (besides electric rickshaws and tempos) to 20 percent.

If this target is achieved, it would decrease Nepal’s fossil fuel imports by 9 percent, a study by the ministry shows.

Experts also suggest adopting electric stoves in our kitchens. These stoves are 60 percent cheaper to buy and operate than LPG ones.

Environmentalist Bhushan Tuladhar advises launching a special campaign to motivate people to switch to electric stoves.

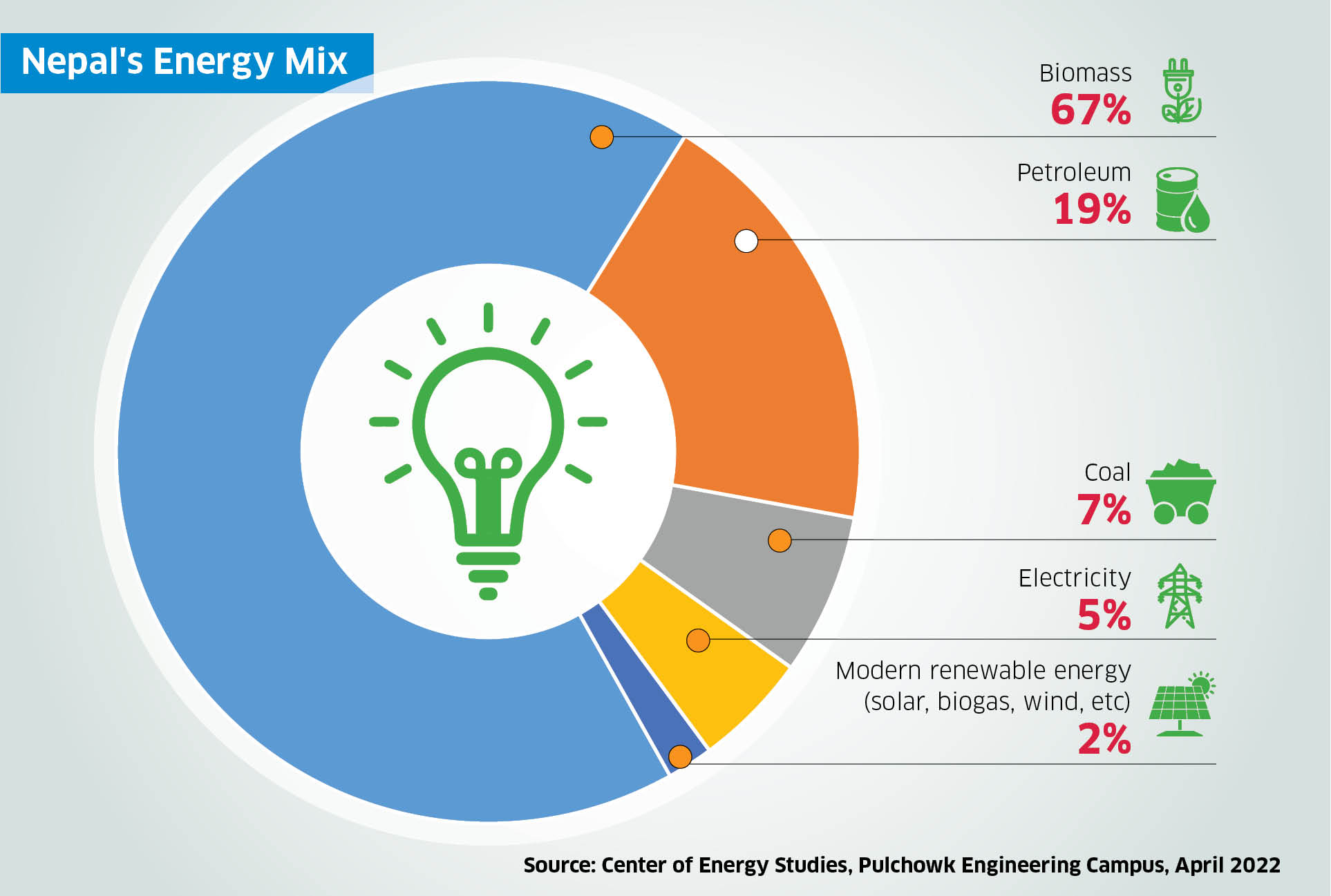

“Instead of exporting electricity to India, we must utilize it in cooking. Around 67 percent of Nepalis still use the smoky biomass to cook. We need to launch a special campaign to switch to clean energy in our kitchens,” he says.

Tuladhar believes local governments have a big role to play in such campaigns.

Nepal has so far earned $25m from carbon trade and this income has been invested in alternative energy. Nepal’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submitted at the United Nations pledges the use of electric stoves as their primary mode of cooking by 25 percent Nepali households by 2030. Similarly, it aims to install 500,000 improved cooking stoves in rural areas by 2025, besides also adding 200,000 household biogas plants and 500 large-scale biogas plants.

There are challenges to transitioning into electric cooking though, such as erratic electricity supply and lack of incentives for those who want to switch.

Pokhrel, of Hydro Village, says oversupply of electricity is damaging transformers and wires in some places, discouraging people from using more of it. Then there is the issue of power cuts.

“People have taken to LGP for cooking purposes as it can be stored and used as and when needed. In the case of electricity, there is no way to ensure its round-the-clock availability,” he says.

Nepal also imports some coal from India, but the exact data is not available.

Deepak Gyawali, former water resource minister, says coal can be produced even in Nepal and there is no need to import it.

“There are legal hurdles to producing commercial coal. But if we can somehow legalize coal production, we can reduce our import bill,” he says.

To cut the consumption of petroleum products, the former minister also suggests a ropeway system for goods transport.

“Right now we are using a transport system that is heavily reliant on petrol and diesel. But we can easily install ropeways and operate them with locally produced electricity,” he adds.

Wind is another source of clean energy but there hasn’t been much study on it in Nepal. Some energy experts reckon Nepal cannot produce enough wind energy to make a significant dent on our fuel import.

There is a hope for solar energy though. The Alternative Energy Promotion Center is taking various initiatives to promote solar and other alternative energy sources.

Nepal right now generates 34 MW electricity from small and micro hydropower projects and 38 MW from solar and wind sources.

Solar could be an alternative in geographically challenged areas where it is difficult to build transmission lines.

Nepal also has international climate obligations to meet as well. The country aims to reach net-zero emissions by 2045 and to this end, it has pledged to cover 15 percent of the total energy demand through clean energy sources.

To achieve this target, drastic and immediate measures are needed to promote homegrown clean energy.

“We cannot completely displace fossil fuels as there are certain areas where we have to continue to use them. But we can substantially decrease their consumption with the right policies and their strict implementation,” says Gyawali, the former water resources minister.

InDepth: Is our energy ecosystem consumer-friendly?

Binod Kumar Bista is a Bachelors of Art (BA) student at Kathmandu’s Ratna Rajyalaxmi College. Originally from a village in Kailali district of far-western Nepal, he lives in a rented room and cooks for himself using LPG. Bista knows the induction stove is more cost-effective and energy-efficient. Yet he is hesitant to make the switch.

“I have limited time for cooking. What if the electricity suddenly goes out?” the 21-year-old asks. “I also cannot afford to have both the options at the same time.”

Research suggests heat-efficiency of induction cookers is nearly 90 percent, while that of conventional gas stoves is 50 percent. The former are also lighter on the consumers’ pockets. A 2021 study conducted by Amrit Man Nakarmi, a professor at the Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University, found that cooking on an induction stove is over 50 percent cheaper than cooking on gas.

Yet Nepalis are reluctant to fully switch to induction cookers. While most urban households rely on LPG for cooking, biomass—at a staggering 67 percent—remains Nepal’s dominant energy source.

What makes people cling to traditional energy sources and is anything being done to change their behavior?

Also read: Possibilities and pitfalls of hydroelectricity

Our energy system doesn’t factor in consumer voice. The authorities dictate whatever they think is right.

At least in the case of biomass and rural electricity distribution, there is more consumer participation in rule-making and enforcement.

Bista’s family in Kailali uses biomass for cooking even though they also have an LPG stove. His family hasn’t fully switched to gas as firewood is both cheaper and more easily available. He says another reason many families in his village prefer firewood to LPG is because they are afraid of possible mishaps from gas-use, while some reckon that food cooked on firewood tastes better.

Dipak Gyawali, former minister of water resources, says it is difficult to get people to move to electricity, but, ultimately, they will have to make the upgrade.

“For example, instead of jumping into electricity from firewood, people in rural areas can start with briquettes or improved cooking. Briquettes are cleaner, forest-friendly, longer burning, and more economical than traditional logs,” he says.

Bharati Pathak, chairman of the Federation of Community Forestry Users Nepal, says while the demand for briquettes and charcoal is high in both urban and rural Nepal, one problem is that the Chinese products have captured the market.

“Many forest products can be used for briquette production. If we could minimize production costs with greater use of technology, the beneficiaries of community forests could benefit a lot financially,” she says.

As for encouraging the LPG-to-electric switch in city areas, the Alternative Energy Promotion Center (APEC) has recently introduced a free induction stove distribution scheme for university students in Kathmandu valley. Almost 13,000 students have applied. An AEPC representative says this scheme will help students adopt induction and change their perception of electric cookers.

Nepal uses most of its energy for cooking and transport purposes. While the use of induction stoves and electric vehicles has been rising, they are still not used in sufficient numbers to achieve energy-efficiency. Many people bought induction stoves when there was a major LPG shortage during the 2015 Indian blockade and at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Similarly, the skyrocketing fuel prices, driven by the Russia-Ukraine war, have persuaded at least some vehicle owners to switch to electric options.

Shrabya Sapkota has been riding a petrol-run scooter for almost five years and is now trying to switch to electric.

“Five rupees of petrol in my scooter gives me a kilometer’s mileage. But if I were to have an electric scooter, I would have to spend just 30 paisa to get the same mileage,” the 22-year-old says. “Say, I do 1,000 km on the road a month. In that case, in three years, I will save around Rs 170,000. Even if I have to replace the e-scooter battery, which costs around Rs 100,000, I still save Rs 70,000.”

But Sapkota represents only a tiny fraction of people who are willing to ditch their fossil fuel-run vehicles for electric ones. There is a general belief that electric vehicles (EVs) are expensive and don’t do well off-road, even though users’ experience suggests otherwise. Consumers are also concerned about the unavailability of charging stations on long-distance travel.

Also read: A snapshot of Nepal’s energy ecosystem

A few electric vehicle companies have opened up charging stations across the country to boost their client numbers—and the approach seems to be working. If other companies follow suit, energy experts expect a significant rise in adoption of EVs.

Brijesh Shrestha, an electric car owner, says humans are by nature resistant to change.

“I too had second thoughts while getting the electric car,” he says. “Many more charging stations and infrastructure should be built to convince folks to go electric.”

The budget for the fiscal 2021/22 had slashed import duties on battery-powered vehicles from 40 percent to 10 percent in a bid to promote their use. Electric vehicles of up to 100kW capacity had to pay 10 percent in custom duties. Likewise, vehicles of 100-200kW capacity paid 15 percent, while 200-300kW vehicles paid 40 percent.

According to the Department of Customs, 1,103 electric cars worth Rs 3.24bn entered Nepal between mid-July to mid-January in the fiscal year. In the same period in the previous fiscal year, only 51 cars valued at Rs 105.19m had been imported.

EV dealers in Nepal see a bright future for electric vehicles: they have been able to meet only 30 percent of demand as India hasn’t been producing enough EVs. But the latest budget has been a dampener.

In its budget for the fiscal year 2022/23, the government significantly hiked excise and customs duties on EVs. A 30 percent customs and 30 percent excise duties have been slapped on EVs of 100-200kW capacity. For electric cars of 201-300kW capacity, customs and excise have been set at 45 percent each. Similarly, excise and custom duties for EVs of over 300kW capacity have been upped to 60 percent each.

This has increased the price of EVs in the Nepali markets, making it difficult for consumers to jump to the electric mode of transport.

Also read: Working out the right combo

Even if people were to move to electric vehicles in droves, there is a lingering concern about the carrying capacity of electricity lines. Nepal’s per capita energy consumption of around 300 units is the lowest in South Asia. This means the country will need a lot of energy in the coming days as it modernizes. Moreover, the current distribution lines are made for lighting purposes, and if people were to switch to electric stoves and vehicles in large numbers, the lines may collapse.

Besides, the consumption of electricity is also growing in rural Nepal.

“The Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) has been unable to provide sufficient electricity in rural areas,” says Mahendra Prasad Chudal, program manager at the National Association of Community Electricity Users-Nepal. “We are trying to sort out a few problems related to bulk-buying and distribution of electricity with the NEA.”

NEA spokesperson Suresh Bahadur Bhattarai says power production is a dynamic process and the agency has been upgrading its system in line with changing demands.

“We have been appealing to the public to switch to electricity. We wouldn’t have done so if our infrastructure couldn’t bear the load,” he says. “To promote electric vehicles, we are also planning to install at least 50 charging stations across the country within the next fiscal year.”

InDepth: Working out the right combo

Nepal’s installed power capacity is expected to exceed 15,000 MW by 2030, according to the Electricity Demand Forecast Report 2017.

By 2040, electricity demand is projected to climb to 82,000 GWh, with a corresponding installed capacity requirement of over 35,000 MW.

Hydropower plants are believed to be Nepal’s most reliable energy-source. In theory, the country can produce 50,000 MW of electricity by harnessing its water resources. But there are challenges galore to turn this theory into practice. For one, cost is a big concern.

Dipak Gyawali, former minister of water resources, says Nepal’s electricity production is three to four times more costly than it is in most other countries. “For instance, Ethiopia started producing electricity without foreign assistance and did it at $800 per kilowatt. In Nepal, we had to fork out $2,500 for the same output,” he says.

Building hydropower plants in Nepal is both challenging and costly because of the country’s difficult hill and mountain topography, often with no road access to the project sites.

“A power plant that takes five years to build elsewhere takes 10 to 15 years in Nepal,” says Gyawali. While technology and expertise have helped reduce both time and cost of building power stations, that is true mostly in the case of storage-type hydropower projects. In Nepal, most hydroelectricity projects are run-of-the-river, which don’t have the desired power storage capacity, or the consistency: During the dry season, electricity production of hydropower stations falls by two-thirds of their peak monsoon-time output.

According to the Department of Electricity Development, Nepal has the electricity generation capacity of 2,094.034 MW, of which 20.18 MW comes from solar sources.

Nepal has set the target of ramping up its clean energy output from 1,400 MW to 1,500 MW by 2030 as part of its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But the achievement of this goal remains doubtful, given the country’s patchy record. Nepal had failed to meet its previous NDC target: to expand renewable energy to 20 percent of its energy-mix by 2020. The share of renewable energy was a mere 3.2 percent in 2019, government data show.

According to a study carried out by the Center of Energy Studies, Pulchowk Engineering Campus, in April 2022, Nepal meets 67 percent of its energy needs from biomass, 19 percent from fossil fuels, seven percent from coal, five percent from electricity, and two percent from alternative sources.

In order to meet the NDC target, say energy experts, Nepal must prioritize clean alternative energy sources alongside hydroelectricity projects.

Solar and biogas technologies could be cheap and viable alternatives, for instance. Solar panels can be set up in each household in a day or two, and approximately a year in case of large-scale production facilities. Likewise, a household biogas system can be installed in two weeks. Madhu Sudan Adhikari, Executive Director of Alternative Energy Promotion Center, believes it is high time Nepal prioritized energy sources other than hydroelectricity to meet its energy needs.

“Generating solar energy is far cheaper than generating hydro energy,” he says. “The cost of building a one MW-capacity hydro plant is around Rs 200m. The same amount of electricity can be generated via solar technology for Rs 70m to Rs 80m.”

But there is a catch. Harnessing the sun’s energy may cost a lot less than generating electricity from water, but solar plants’ power availability factor—a measure of efficiency—of 18 to 20 percent dwarfs that of hydropower stations at 30 to 40 percent. There is invariably a trade-off.

Jagan Nath Shrestha, a solar energy expert, believes both hydro and solar plants can be simultaneously developed, so that energy production does not fluctuate.

Also, finding a large enough area to set up solar panels to support large communities is a big concern, especially in a crowded city like Kathmandu where open spaces are rare.

But this problem also has a solution, says Shrestha. “If, say, 100,000 of the bigger, well-spread houses in Kathmandu valley install solar panels, the surplus electricity they produce can be used to offset any shortfall in the national grid,” he adds.

Better yet, say energy experts, solar technology should work in concert with the biogas systems in rural Nepal where most families still rely on traditional, polluting energy sources like firewood.

It is more costly to install solar panels in individual rural households compared to their installation cost for urban households. But there is plenty of space available in non-urban areas of Nepal to set up small- to medium-size solar facilities to light up small communities. And for biogas systems, they already have easy access to organic materials.

“It takes approximately Rs 100,000 for a household to set up a biogas system for cooking or heating purposes,” says Shekhar Aryal, chairperson of Biogas Sector Partnership-Nepal.

According to Aryal, nearly 1.4m rural households in Nepal have the capacity to produce biogas (at present, only half a million do).

Mass-produced and environmentally-friendly briquettes—compressed blocks of coal dust or renewable products such as paper, sawdust, wood chips and agricultural wastes—can also come handy as many rural areas are inclined towards traditional energy production.

Both hydro and alternative energy sources have their benefits and drawbacks. The goal is not to choose one over the other, suggest energy experts, but to come up with the right mix so as to meet our household and industrial power needs while keeping our environment sufficiently clean.

InDepth: A snapshot of Nepal’s energy ecosystem

Modern life is unthinkable without energy-power. We need energy to cook food, to get to our offices and even to enjoy our favorite movies. As such, with growing urbanization, Nepal’s energy needs are also increasing.

The country gets its energy from various sources, mainly hydro plants, fossil fuel, sun and biomass.

Hydro plants

The government-owned Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) is the main stakeholder of most hydropower plants in Nepal.

The country has two types of hydropower plants: micro and large. Large-scale hydropower generation started with a 500kW capacity plant in Pharping in 1911. It was followed by two other projects in Sundarijal (1936) and Panauti (1965), respectively.

Eight decades after the start of the first hydropower project, the government introduced the Hydropower Development Policy in 1992, inviting both domestic and foreign private investment. There are now 113 working large-scale hydropower stations in Nepal.

The NEA was formed on 16 Aug 1985 under the Nepal Electricity Authority Act 1984. It came to being following the merger of the Department of Electricity under the Ministry of Water Resources, the Nepal Electricity Corporation, and other related development boards, with the goal of creating a consolidated, one-stop organization.

The NEA’s primary objective is to generate, transmit and distribute adequate, reliable, and affordable power by planning, constructing, operating, and maintaining all generation, transmission, and distribution facilities in Nepal’s power system.

Micro-hydro plants have been installed in Nepal since the 1960s, mainly for agro-processing, with locally developed turbines replacing diesel engines. The Agriculture Development Bank Nepal also started providing loans to village entrepreneurs to set up paddy mills, oil expellers, etc. But until 1980, the focus was primarily on large-scale hydro stations.

In 1981, the government started subsidizing micro-hydro plants, with a subsequent boost in their number. Several turbine mills were fitted with a small dynamo to generate electricity in what were mostly off-grid, isolated plants serving local villages.

Office of Alternative Energy Promotion Center (AEPC) in Mid-baneshwor, Kathmandu | Photo: Pratik Rayamajhi

Office of Alternative Energy Promotion Center (AEPC) in Mid-baneshwor, Kathmandu | Photo: Pratik Rayamajhi

In 2000, the Alternative Energy Promotion Center (AEPC) was formed to look after the 10-100kW micro-hydro power plants. The objective was to generate renewable energy and boost efficiency of energy resources to improve the living conditions of people and combat climate change.

The center also works on the development of commercially viable alternative energy industries. Besides hydropower, it focuses on other renewable energy sources like solar, wind, improved biomass, and biogas.

In 2015, the NEA and the APEC agreed to join the Syaurah Bhumi Micro Hydro Project (23kW) to the national grid. The project came on steam on 11 January 2018, delivering 178,245 units of electricity annually. As of now, there are 17 micro-hydropower power plants in Nepal.

Ajoy Karki, director at Sanima Hydro and Engineering, a hydropower consultant, says micro-hydro projects were all the rage until a decade ago but investors these days prefer larger-scale projects.

“As important and profitable micro-hydro projects are, larger investments in big projects result in bigger profits, too” he says.

Karki is of the view that people in rural Nepal should collectively invest in micro-hydro, and with the help of local governments seek to generate both electricity and capital.

Half a million households from 54 districts across Nepal use community electricity via the Community Rural Electricity Entities (CREEs)—with the National Association of Community Electricity Users-Nepal (NACEUN) as their primary stakeholder.

CREEs buys electricity from NEA in bulk and distributes it to remote consumers. The organization currently has a network of over 300 CREEs.

Vidhyut Utpadan Company Ltd, Rastriya Prasaran Grid Company Ltd, and Hydroelectricity Investment and Development Company Ltd are the other major government stakeholders in Nepal’s hydroelectricity generation.

Petroleum products

The state-monopoly Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC) was established in 1970 to import, store and distribute petroleum products throughout the country.

Nepal depends on import of refined petroleum products from the Indian Oil Corporation (IOC). Besides the NOC, no other public or private entity is allowed to import petroleum products.

The NOC renews its agreement with the IOC every five years for the smooth supply of petroleum products. LPG is imported from privately-owned bottling industries from different parts of India under an NOC product-delivery order.

According to the NOC, Nepal currently consumes 150,000kl of diesel and 60,000kl of petrol a month, with a total burden of Rs 30bn on the exchequer. In recent times, the import of petroleum products–largely consumed by households, motor vehicles and industries–has increased by 15 percent a year.

In the fiscal 2020-21, Nepal’s consumption of petrol, diesel, kerosene, aviation fuel, and LPG was 587,677kl, 1,698,427kl, 23,427kl, 70,400kl and 477,753mt respectively, informs petroleum products expert Chakra Bahadur Khadka. “We must act immediately to reduce this consumption by switching to renewable energies as import of fossil fuels helps neither our foreign reserve nor the environment.”

The corporation incurs a per-liter loss of Rs 24.70 on petrol and Rs 18.01 on diesel used in public transport, industry and projects. In LPG alone, it incurs a loss of Rs 751.14 a cylinder.

Wind-solar hybrid power system in the Hariharpurgadi village of Sindhuli district, financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Wind-solar hybrid power system in the Hariharpurgadi village of Sindhuli district, financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Solar and wind

Various studies suggest Nepal has great potential in solar energy, but the country has yet to realize this potential. It is said that Nepal can generate up to 50,000 terawatt of solar power annually–100 times what can be generated from our rivers and 7,000 times the current electricity consumption.

Anecdotally, solar panels were first installed at Bhadrapur Airport in Jhapa district in 1962. Officially, solar panels officially came into operation from Damauli Telecommunication Office (then Aakashbani) in 1975.

Solar energy started off as a household energy source before recently making its way to the national grid–where it is making only a small contribution.

In 2020, the government inaugurated the first phase of its first 25MW solar array that feeds electricity directly into the national grid, in what is the biggest among the four large-scale solar power plants the NEA has launched. A few other private entities are also contributing to the development of solar energy in rural areas via community-based projects. Some of them send the surplus power to the national grid.

According to new laws, any household can produce electricity (without installing batteries) and send surplus energy to the nearby national grid. But many people are unaware of this scheme due to lack of publicity.

“Say, 100,000 houses of rich people in Kathmandu install solar panels. In that case, the surplus energy they generate could meet a sizable chunk of the valley’s energy needs,” says Jagan Nath Shrestha, a solar energy expert.

Part of why solar energy is not attracting investment in Nepal, Shrestha says, is the pricing.

“The price of a unit of solar electricity was Rs 9. But the rate was inexplicably reduced to Rs 6 a unit. At this rate, it may not be viable for the private sector to supply to the national grid,” he adds.

As for wind energy, Nepal is still in its early days. While the AEPC has installed wind turbines in a few areas, they are not completely wind-driven. As wind flow is not uniform across Nepal, these power stations also rely on solar energy.

A couple of decades ago, wind turbines were installed in Mustang district. But they were damaged due to excessive wind.

“The private sector is not interested in wind-power as there is no security of their investment,” says Madhusudhan Adhikari, executive director of the APEC.

A biogas plant installed in a house of Madhes province | Photo: Renewable World

A biogas plant installed in a house of Madhes province | Photo: Renewable World

Biogas

Most rural households in Nepal still rely on firewood for cooking. Energy experts and environmentalists see biogas as a viable alternative to this. Biogas is a form of clean, eco-friendly source of renewable energy which is both economically and environmentally viable.

It is produced from organic waste and can be used for multiple purposes. For example, the slurry that the biogas system produces is a convenient source of organic fertilizer. The energy of biogas could also be used as a fuel for heating purposes other than cooking. It can be compressed, much like natural gas, and used to power motor vehicles as well.

The commercial beginning of biogas in Nepal can be traced back to a program carried out by the United Missions to Nepal in the context of the Agricultural Year 1974/1975. The Agricultural Development Bank Nepal assisted in financing the plants by providing a special credit framework and established the Gobar Gas Company in 1977.

Biogas technology can also generate plenty of green jobs in Nepal. Most villages in Nepal have biogas plants. Studies show that biogas plant installation goes hand in hand with the improvement in local health and sanitation measures, while also curbing deforestation.

But biogas use is not widespread, with firewood still the main source of cooking fuel in rural Nepal.

Even when 1.4m rural houses of Nepal can potentially use biogas technology, only half a million households have installed it, says Shekhar Aryal, chairperson of Biogas Sector Partnership-Nepal.

“The cost of biogas technology, with nearly Rs 100,000 needed to install a plant, has increased with time, which in turn has reduced its attractiveness for villagers,” he says.

“This technology will live up to its potential only when the government gives them enough subsidies,” Aryal adds.